|

|

Alison Smith with Robert Upstone,

Michael Hatt, Martin Myrone, Virginia Dodier, Tim Batchelor; Exposed -

The Victorian Nude (Watson-Guptill Publications, 2001)

The primary value

of exhibition catalogs lies in the illustrations of the works, accompanied

by some information about the circumstances of their creation and the

artists’ biographies. This satisfies a particular in need in cases like the

Tate’s exhibition of the Victorian nude since many of the works are in

private collections or small provincial museums, and accordingly have never

before been illustrated. In this light Exposed is a valuable

document.

The actual text, if it is to be worth our

time, should, in addition, be long on fact and short on opinion, especially

in the case of the 19th century nude where – in a situation of

academic faggotry run wild – the verbiage of aesthetic disapproval is often

used to mask religious and moral prejudice.

In this respect, the commentary of Smith and her

confrères is agreeably even-handed and largely ignores the digladiations of

the odious Steinem and her ilk. It is against this temperate background that

I suggest corrections in those cases where I find the influence of the

intolerant has broken through.

Both instances of repugnant observation are the work of

Virginia Dodier from New Mexico and, perhaps incidentally, both cases have

to do with photography. Regarding  (No. 89),

Plüschow’s lovely portrait of four Italian girls, Dodier says, "This image

of four pre-pubescent, beautiful and undoubtedly poor Italian girls

completely undressed and standing against a wall conveys a palpable sense of

discomfort and vulnerability, degradation and humiliation – key ingredients

in pornography. We do not know who they are or how they were induced to pose

for Plüschow, nor if they posed on more than one occasion or worked for

other photographers. Surely they were paid, whether in money or in food."

Bullshit. There’s nothing like doing a little research if you’re going to be

an art historian. Two of the models may very well have posed for this

Plüschow photo (No. 89),

Plüschow’s lovely portrait of four Italian girls, Dodier says, "This image

of four pre-pubescent, beautiful and undoubtedly poor Italian girls

completely undressed and standing against a wall conveys a palpable sense of

discomfort and vulnerability, degradation and humiliation – key ingredients

in pornography. We do not know who they are or how they were induced to pose

for Plüschow, nor if they posed on more than one occasion or worked for

other photographers. Surely they were paid, whether in money or in food."

Bullshit. There’s nothing like doing a little research if you’re going to be

an art historian. Two of the models may very well have posed for this

Plüschow photo  as well

where their obviously posed looks of distress should warn us against drawing

hasty conclusions from facial expressions. And if they are in this

photo as well

where their obviously posed looks of distress should warn us against drawing

hasty conclusions from facial expressions. And if they are in this

photo  they look

anything but vulnerable, degraded and humiliated. In fact they seem to be

quite enjoying themselves. While we’re at it, why are

"discomfort…vulnerability, degradation and humiliation" "key ingredients in

pornography" I rather enjoy pornography, but the last time I checked I

didn’t much enjoy feelings of discomfort. Perhaps there are those who get an

erotic thrill from images of vulnerability et al. (de gustibus and

all that), but those "key ingredients" would disqualify 99% of sexy and nude

photos (presumably even those of children) since their subjects don’t really

appear to experience vulnerability etc. (unless you stipulate that being

undressed analytically entails vulnerability). Incidentally, by Dodier’s

bizarre definition, they look

anything but vulnerable, degraded and humiliated. In fact they seem to be

quite enjoying themselves. While we’re at it, why are

"discomfort…vulnerability, degradation and humiliation" "key ingredients in

pornography" I rather enjoy pornography, but the last time I checked I

didn’t much enjoy feelings of discomfort. Perhaps there are those who get an

erotic thrill from images of vulnerability et al. (de gustibus and

all that), but those "key ingredients" would disqualify 99% of sexy and nude

photos (presumably even those of children) since their subjects don’t really

appear to experience vulnerability etc. (unless you stipulate that being

undressed analytically entails vulnerability). Incidentally, by Dodier’s

bizarre definition,

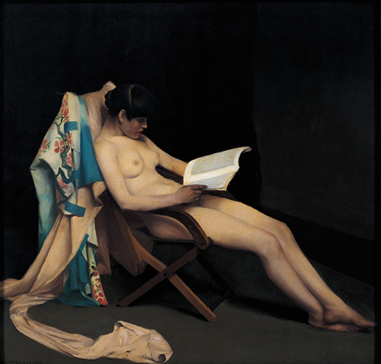

is

pornography but is

pornography but

is

not. is

not.

In fact the models don’t look vulnerable, degraded and

humiliated in No. 89 either. They have your basic Children Posing for 19th

Century Photos look, not unlike the Fatima urchins:

.

If any criticisms could be leveled at No. 89, it is that the figure on the

left should be cropped out. Her eyes are unfortunately closed and the other

three form a kind of Three Graces frieze. But that’s as may be. Still, isn’t

it possible that the girls actually had fun posing for these photos? And

indeed there is nothing wrong with accepting pay for anything you do. On the

contrary. .

If any criticisms could be leveled at No. 89, it is that the figure on the

left should be cropped out. Her eyes are unfortunately closed and the other

three form a kind of Three Graces frieze. But that’s as may be. Still, isn’t

it possible that the girls actually had fun posing for these photos? And

indeed there is nothing wrong with accepting pay for anything you do. On the

contrary.

And then there is the gratuitous and unfounded comment

that the girls were “undoubtedly poor” and working for food. Dodier

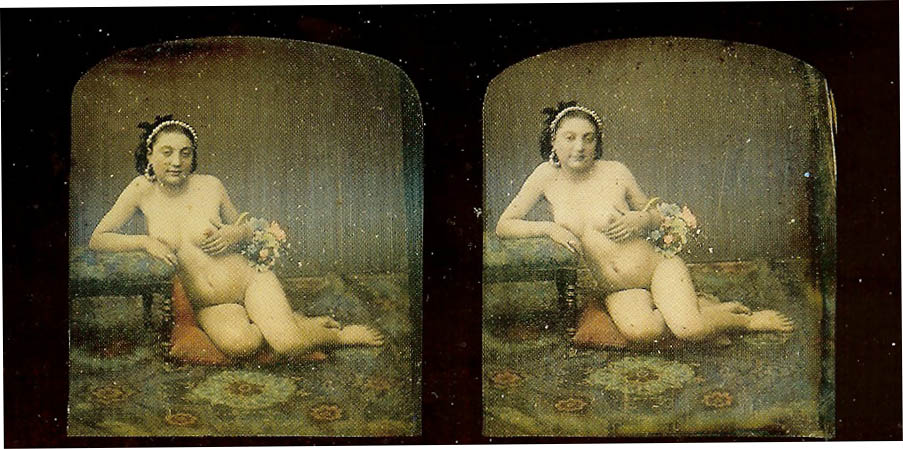

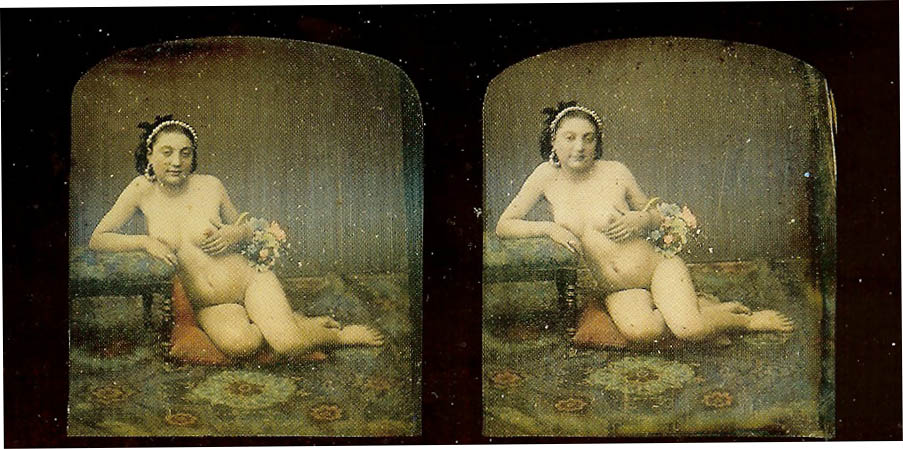

reiterates her bluestocking social snobbery regarding  (No. 91),

where she says that the model was "probably working class" and adds "It can

be assumed that the photographer was male, that the purchaser was male and

affluent, that the model was paid for posing, and that the photographer made

a profit." Oh, those horrible men! I thought historians didn’t "assume"

anything, that they looked up the records and, if they couldn’t establish

the facts, they shut up, especially if their assumptions are intentionally

inflammatory. Dodier practices what might be called George Bush art history,

viz. if you don’t have the facts, just make a few up to establish your point

because Jesus would want it that way. And again, what’s wrong with selling

your services and making a profit (although personally I would not pay good

money for a photo of the model in No. 91). Dodier’s social assumptions are

pure regurgitated Karl Marx; I assume she’s just another one of those artsy

America haters. (No. 91),

where she says that the model was "probably working class" and adds "It can

be assumed that the photographer was male, that the purchaser was male and

affluent, that the model was paid for posing, and that the photographer made

a profit." Oh, those horrible men! I thought historians didn’t "assume"

anything, that they looked up the records and, if they couldn’t establish

the facts, they shut up, especially if their assumptions are intentionally

inflammatory. Dodier practices what might be called George Bush art history,

viz. if you don’t have the facts, just make a few up to establish your point

because Jesus would want it that way. And again, what’s wrong with selling

your services and making a profit (although personally I would not pay good

money for a photo of the model in No. 91). Dodier’s social assumptions are

pure regurgitated Karl Marx; I assume she’s just another one of those artsy

America haters.

But why are we supposed to care what social class they

came from? Why make the comment? When I go to galleries or museums I don’t

run around wondering what social class the models sprung from (although I

think some English people do). Is it just because they are nude? I doubt

whether Dodier would waste ink speculating about the the social standing of

the children in Bouguereau’s

Sur la grève, or insinuating what a

horrible exploiter of children the artist was. (Incidentally Plüschow’s

photograph is far superior to Bouguereau’s painting.)

Presumably the idea is that being nude, or at least

posing nude, is irredeemably Working Class, indulged in only by women so

bestialized they would happily lick their own pussies for a crust of stale

bread. But, as other works in the exhibition show, the models we know

something about, largely the English models, were sometimes other artists

like Hetty Pettigrew and quite often women of exceptional self-possession

and lively intelligence. Why not extend this assumption to the Italian

girls? Is it because they are Italian and the Italians are closer to beasts

than the English (or New Mexicans) are? Dodier refrains from this sort of

racist insinuation in her comments on Plüschow and von Gloeden’s photos of

Italian boys. I suppose women in her view are just inferior.

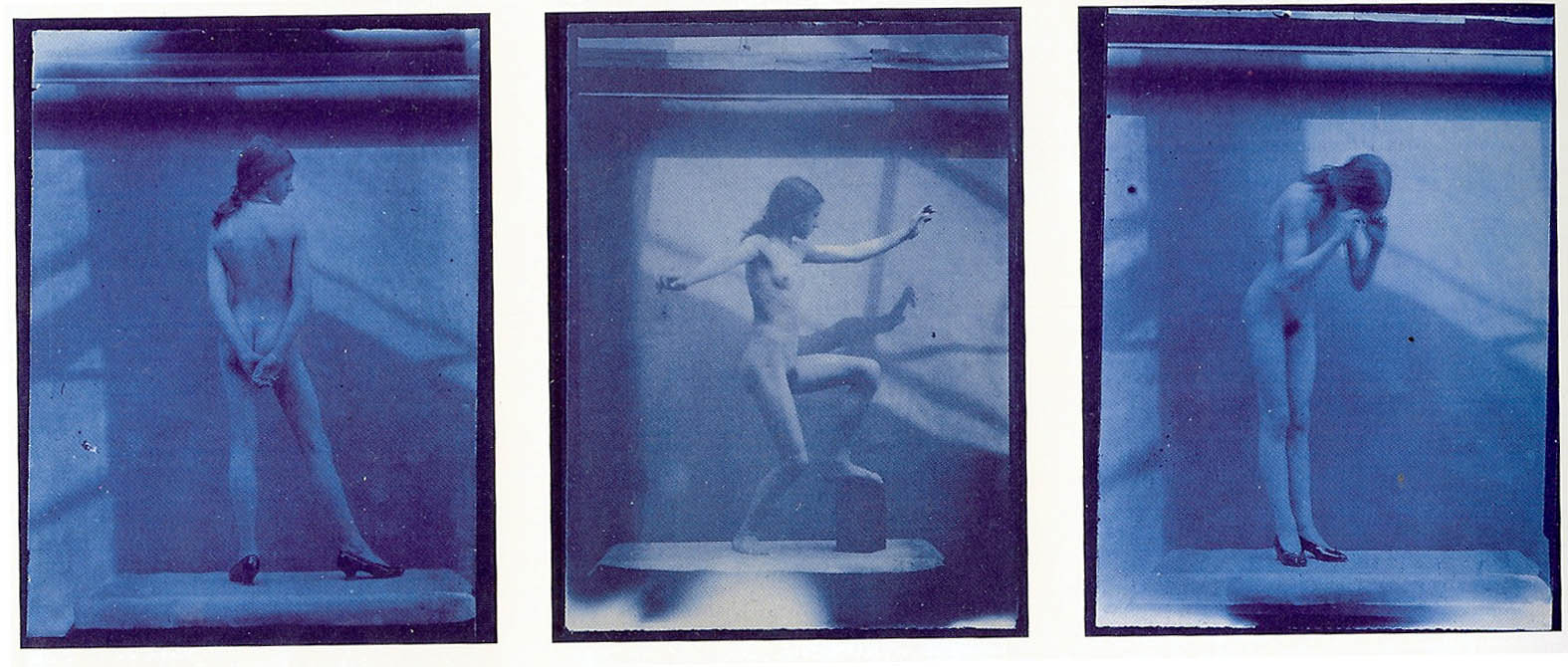

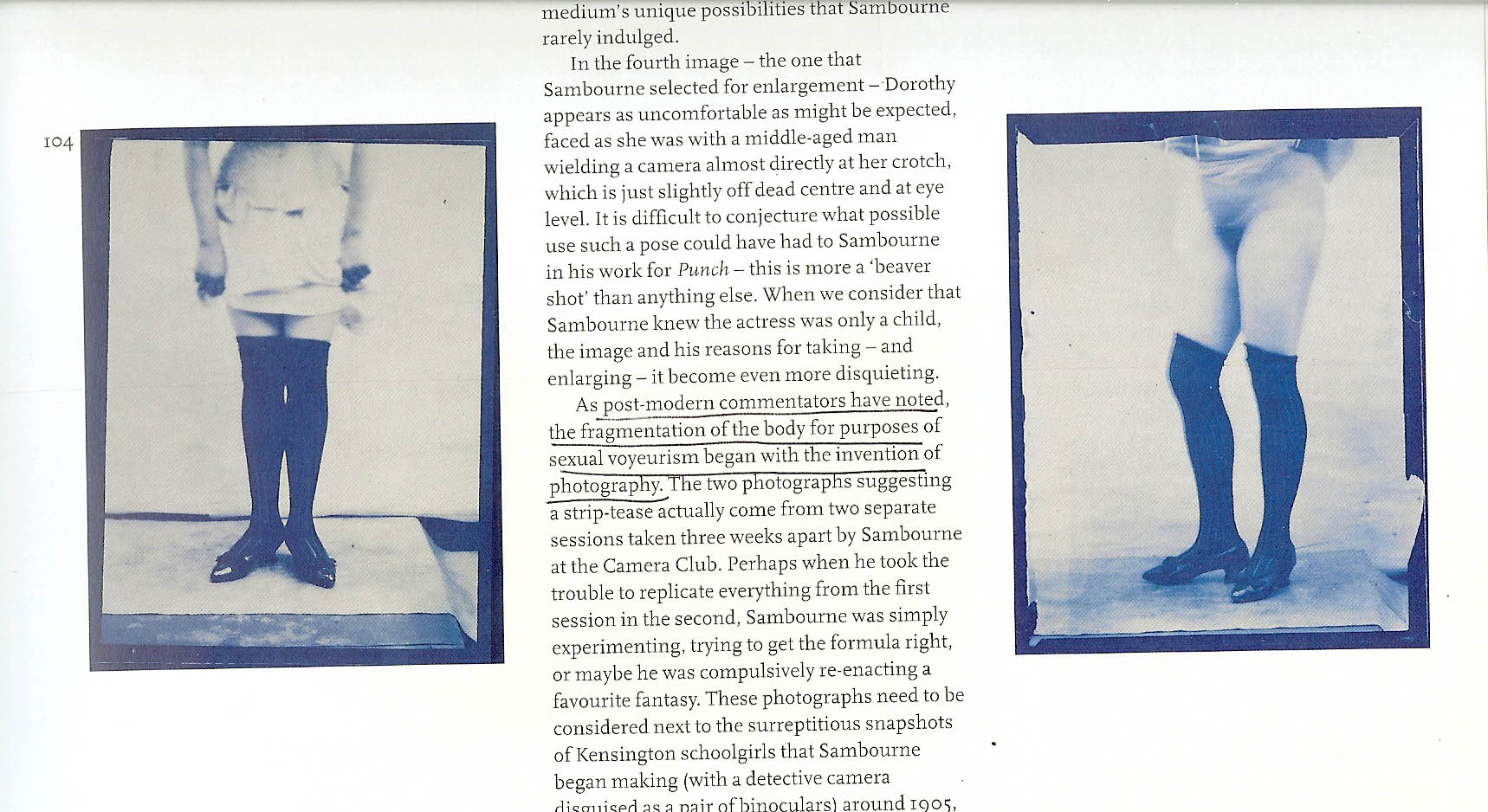

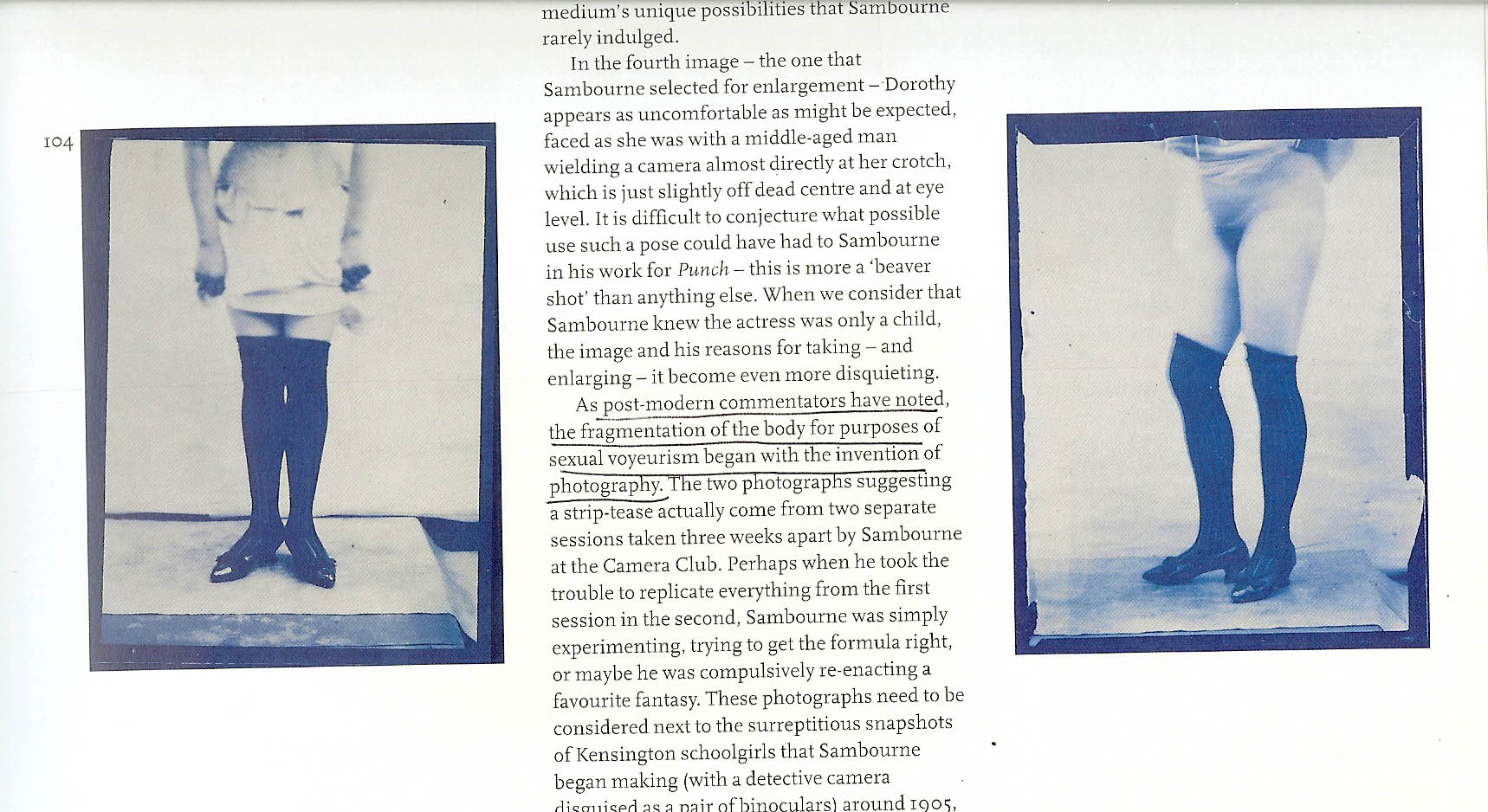

Dodier returns to the fray in her comments of Edward

Linley Sambourne’s nude photos

Nos.100-105), but this commentary replaces racism with a similar age-related

prejudice. The works on exhibit include a series with a model named Dorothy

and two fake (because they were obviously shot in a studio) upskirt

photographs Nos.100-105), but this commentary replaces racism with a similar age-related

prejudice. The works on exhibit include a series with a model named Dorothy

and two fake (because they were obviously shot in a studio) upskirt

photographs

. One of

the Dorothy photographs showed her pussy but seems to have been cropped to

include her face (We cannot tell because prudery or feminazism (The two are

indistinguishable, really) caused it to be excluded from the exhibition).

Dodier writes, "It is difficult to conjecture what possible use such a pose

could have had to Sambourne in his work for Punch – this is more a

‘beaver shot’ than anything else. When we consider that Sambourne knew the

actress was only a child, the image and his reasons for taking – and

enlarging – it become even more disquieting." She adds à propos of

the upskirt photos, "As post-modern commentators have noted, the

fragmentation of the body for the purposes of sexual voyeurism began with

the invention of photography." Once again Dodier lets her own "Victorianism"

get in the way of responsible scholarship. Why are these photos supposed to

have anything to do with Punch? Art is usually created for the

pleasure of the thing and attractive nude women are a pleasurable sight.

Sambourne’s age is irrelevant unless one assumes that the "middle-aged" –

and indeed the elderly – should be denied sexual pleasure. In fact Dorothy’s

youth seems to contribute to her attractiveness, since 19th

century artists were struggling to escape the big butt canons of proportion

that came down from the Renaissance, and one of their means was precisely

the observation of real women, their models, instead of relying on ruler and

compass guides to human proportions. Dorothy’s pictured "aplomb" has two

sources worth noting. On the one hand Sambourne was clearly trying to escape

from the stiffness of much portrait photography due in large part to the

clumsiness of available photographic techniques. Clearly film speed and

contrast control had improved to the extent that Sambourne could take "42"

shots of the models in one sitting (No. 96) and the models could assume

poses (Nos. 98 and 99) that could not have been held for too long with any

degree of spontaneity. It also allowed Dorothy to move in front of the

camera, even though she had to pause for each shot, and thus provide an

initial taste of the potential for photographic models. It is perhaps

unfortunate that Sambourne chose to experiment with high contrast lighting

from the skylight, which might be responsible for the murkiness of the

photos. On the other, the immense speed and flexibility of photography

compared to studio painting and even sketching allowed artists to experiment

freely with poses and compositions because they were no longer held back by

the great investment of time required by manual techniques. The three

exhibited Dorothy poses were the work of an afternoon, and one can only

speculate how many decades - or centuries – would have had to elapse before

painting or sculpture could have evolved away from endless Knidian

imitations to dabble in these offbeat poses. . One of

the Dorothy photographs showed her pussy but seems to have been cropped to

include her face (We cannot tell because prudery or feminazism (The two are

indistinguishable, really) caused it to be excluded from the exhibition).

Dodier writes, "It is difficult to conjecture what possible use such a pose

could have had to Sambourne in his work for Punch – this is more a

‘beaver shot’ than anything else. When we consider that Sambourne knew the

actress was only a child, the image and his reasons for taking – and

enlarging – it become even more disquieting." She adds à propos of

the upskirt photos, "As post-modern commentators have noted, the

fragmentation of the body for the purposes of sexual voyeurism began with

the invention of photography." Once again Dodier lets her own "Victorianism"

get in the way of responsible scholarship. Why are these photos supposed to

have anything to do with Punch? Art is usually created for the

pleasure of the thing and attractive nude women are a pleasurable sight.

Sambourne’s age is irrelevant unless one assumes that the "middle-aged" –

and indeed the elderly – should be denied sexual pleasure. In fact Dorothy’s

youth seems to contribute to her attractiveness, since 19th

century artists were struggling to escape the big butt canons of proportion

that came down from the Renaissance, and one of their means was precisely

the observation of real women, their models, instead of relying on ruler and

compass guides to human proportions. Dorothy’s pictured "aplomb" has two

sources worth noting. On the one hand Sambourne was clearly trying to escape

from the stiffness of much portrait photography due in large part to the

clumsiness of available photographic techniques. Clearly film speed and

contrast control had improved to the extent that Sambourne could take "42"

shots of the models in one sitting (No. 96) and the models could assume

poses (Nos. 98 and 99) that could not have been held for too long with any

degree of spontaneity. It also allowed Dorothy to move in front of the

camera, even though she had to pause for each shot, and thus provide an

initial taste of the potential for photographic models. It is perhaps

unfortunate that Sambourne chose to experiment with high contrast lighting

from the skylight, which might be responsible for the murkiness of the

photos. On the other, the immense speed and flexibility of photography

compared to studio painting and even sketching allowed artists to experiment

freely with poses and compositions because they were no longer held back by

the great investment of time required by manual techniques. The three

exhibited Dorothy poses were the work of an afternoon, and one can only

speculate how many decades - or centuries – would have had to elapse before

painting or sculpture could have evolved away from endless Knidian

imitations to dabble in these offbeat poses.

As regards these post-modernist commentators,

references are lacking so we have no idea whom Dodier is talking about (Nochlin?).

But whoever, they may be, somebody is just flat wrong. If the pompous

academic phrase "fragmentation of the body" is supposed to mean images of

body parts, the source is by and large the Japanese print as mediated by

Degas and the motive is not particularly difficult to state. Artists were

and are looking for what they refer to as a more graphic composition, namely

a flatter pictorial space unlike the artificial stage space of Old Master

painting. Body parts are a semi-abstract result of this quest, reaching

extremes in artists like Georgia O’Keefe. Another source is advertisers’

desire to show particular products. If you want to sell rings, you use a

hand model; if you want to sell lipstick, you shoot lips. Exhibiting these

products via the un-"fragmented" image of a model’s entire body would be

just loony. Also unexplained is the meaning of the sinister sneer behind

phrases like "fragmentation of the body" and "sexual voyeurism." I suppose

she means that people get an additional sexual excitement from seeing a

fingernail, for example, and not the rest of a woman’s body. I suppose that

is true for some people, though I for one usually am more turned on by

photos that include a model’s face. In fact when photographers include

photos of body parts in a layout, it is usually for variety. A combination

of long and tight shots provides pace to a photographic layout. The same

camera distance throughout would simply be boring. Close ups of cunt and tit

are exciting for the same reason we like to get close to cunt and tit during

sex. But they are more exciting if photos showing the whole model including

her face accompany them. Dodier and her "post-modern commentators" also seem

to be making the nasty and unstated (unstated because all you have to do is

say it out loud to expose its absurdity) insinuation that "sexual voyeurs"

enjoy images of body parts because it either makes the model anonymous or

allows the viewer to engage in some sort of sadistic Jack the Ripper

fantasy. When you see a cropped photo of a pussy, you see, you are really

butchering the poor young thing in your imagination. Maybe there are people

like that (Krafft-Ebbing may have a few examples), but I venture to say, not

many. I personally prefer intact bodies and I personally find a pleasant

personality (or the painterly index of a pleasant personality) more

stimulating than pure neutrality (One reason that Picasso’s nudes are

neither arousing nor disturbing is the distortion makes them neutral; they

are not real women). But I’ll take neutrality over a bitch any time.

|