|

|

Random content

Fuckin’

the Servants

Tolstoy on Sex and

Death

Never trust a desperate man.

On p. 254 of

Sein und

Zeit Heidegger inserts a footnote to the effect that in

The Death of Ivan Ilyich Tolstoy

depicts the disruption (Erschütterung) and collapse (Zusammenbruch)

of the phrase (or phenomenon), “‘one dies’ (‘People die,’ ‘Somebody is

dying,’ ‘man stirbt’)” What does he mean?

“One dies” is an expression

Heidegger associates with an approach to death that he clearly dislikes (or

at least he piles on qualifications that I would consider disapproving). The

expression can be unpacked in several different ways. It can mean, “Somebody

is dying,” such as you might say to a telemarketer who called just as your

Uncle Billy was in the last stages of his pneumonia. Or else it can mean,

“People die” in the sense of a non-emotionally charged statement of fact on

the order of “Horses have four legs.” But you can also say “People die” with

a shrug the shoulders and a resigned glance off camera.

The attitude exemplified by

the expression “People die” in some combination of the last two senses is

what Heidegger finds a despicable albeit essential part of the structure of

that aspect of human existence (Dasein) he calls “They” (das Man).

The footnote implies that Tolstoy’s short story depicts the disruption or

undoing of this attitude. Something in the story confirms Heidegger’s

disapproving description of the everyday (usual, common or garden,

alltäglich) approach to death.

I feel fairly certain, based

on the overtones of what Heidegger says and the overtones of Tolstoy’s

narrative attitude, that the exemplars of the everyday attitude include the

following persons and events – even though Heidegger does not confirm my

fair degree of certainty by citing specific passages:

When Ivan’s colleagues are

informed of the news of his death, their thoughts immediately turn to who

will fill his post and to their own careers and concerns. Ivan’s death is

viewed as an event in the world of the living followed by succeeding events

some of which are causally influenced by the fact of his death.

So on receiving the news of Ivan Ilyich’s death the first thought of each of

the gentlemen in that private room was the changes and promotions it might

occasion among themselves or their acquaintances.

‘I shall be sure to get Shtabel’s place or Vinnikov’s,’ thought Fëdor

Vasilievich. ‘I was promised that long ago, and the promotion means an extra

eight hundred rubles a year for me besides the allowance.’

‘Now I must apply for my brother-in-law’s transfer from Kaluga,’ thought

Peter Ivanovich. ‘My wife will be very glad, and then she won’t be able to

say that I never do anything for her relations.’ (p. 96)

These characters do feel a

pang of the fear of death, expressed as a happiness that someone else died.

That pang is quickly replaced by concerns about attending the funeral.

Besides considerations as to the possible transfers and promotions likely to

result from Ivan Ilyich’s death, the mere fact of the death of a near

acquaintance aroused, as usual, in all who heard it the complacent feeling

that, ‘it is he who is dead and not I.’

Each one thought or felt, ‘Well, he’s dead but I’m alive!’ But the more

intimate of Ivan Ilyich’s acquaintances, his so-called friends, could not

help thinking also that they would now have to fulfill the very tiresome

demands of propriety by attending the funeral service and paying a visit of

condolence to the widow. (pp. 96-97)

Peter Ivanovich is the only

one among the aforementioned colleagues to attend Ivan Ilyich’s wake. His

encounter with a mutual acquaintance in the house is described as follows:

His

colleague Schwartz was just coming downstairs, but on seeing Peter Ivanovich

enter he stopped and winked at him as if to say: ‘Ivan Ilyich has made a

mess of things – not like you and me.’

Peter Ivanovich allowed the ladies to precede him and slowly followed them

upstairs. Schwartz did not come down but remained where he was, and Peter

Ivanovich understood that he wanted to arrange where they should play bridge

that evening. (p. 97)

(This by the way sounds much like, and may be the

source of Heidegger’s comment that, as far as “most people” (das Man)

are concerned, a person who dies is simply being bothersome (Unannehmlichkeit)

and tactless (Taktlosigkeit). Tolstoy reinforces that point a bit

later when he describes the angry offended expressions on the faces of Ivan

Ilyich’s daughter and her fiancé.) Schwartz’s real concerns are elaborated a

few paragraphs later when he tries to invite the apparently exiting Peter

Ivanovich to that bridge game.

His

very look said that this incidence of a church service for Ivan Ilyich could

not be a sufficient reason for infringing the order of the session – in

other words, that it would certainly not prevent his unwrapping a new pack

of cards and shuffling them that evening….there was no reason for supposing

that this incident would hinder their spending the evening agreeably. (p.

99)

Peter Ivanovich closes

Tolstoy’s circle of irony (at the same time making clear that, though the

opening passages are depicted through his eyes, his is not the moral

perspective of the narrator) by leaving the funeral to join the bridge game.

Along the way, he proves unhelpful to Ivan’s wife, Praskovya Fëdorovna, in

her search for an enhanced death benefit from the government. The comic

scene between the two that begins with a less than flattering description of

her looks and ends with her abrupt dismissal of Peter Ivanovich, places her

squarely among the Alltäglichkeit crowd.

As for Peter Ivanovich, he

does have a momentary brush with Tolstoy’s point of view, but he manages to

pull himself together and get back with the program (which Tolstoy qualifies

as a “customary reflection”).

The

thought of the sufferings of this man he had known so intimately, first as a

merry little boy, then as a school-mate, and later as a grown-up colleague,

suddenly struck Peter Ivanovich with horror, despite an unpleasant

consciousness of his own and this woman’s dissimulation. He again saw that

brow, and that nose, pressing down on the lip, and felt afraid for himself.

‘Three days of frightful

suffering and then death! Why, that might suddenly, at any time, happen to

me,’ he thought, and for a moment he felt terrified. But – he did not

himself know how – the customary reflection at once occurred to him that

this had happened to Ivan Ilyich and not to him, and that it should not and

could not happen to him, and that to think that it could would be yielding

to depression which he ought not to do, as Schwartz’s expression plainly

showed. After which reflection Peter Ivanovich felt reassured, and began to

ask with interest about the details of Ivan Ilyich’s death, as though death

was an accident natural to Ivan Ilyich but certainly not to himself. (pp.

101-102)

A few phrases used to

describe Ivan Ilyich’s life point up that, though Tolstoy’s disapproval

might be general, it is also aimed at a specific class of Russian society.

The story of his life is described as “most simple, most ordinary” (All

quotes pp. 104 ff.) and adjectives like “easy and agreeable,” “correct,”

“good breeding” are sprinkled though the text. He does his work comme il

faut (There is an interesting comparison between Tolstoy’s use of

comme il faut and Balzac’s. By living a life comme il faut,

Tolsoy means doing everything by the rules, not making waves and getting

ahead in a comfortable sort of way. By une femme comme il faut,

Balzac means any non-working class or peasant woman who was not a kept woman

or given to serial lovers, basically a faithful bourgeoise or

aristocrat) and in fulfillment of his duty as defined by “those in

authority.” His marriage was “considered the right thing” and his wife

“thoroughly correct.” Ivan strives for “a decorous life approved by

society.” Indeed Ivan is presented as having a lot of the traits saliently

highlighted about Oblonsky and also Vronsky in Anna Karenina.

Ivan Ilyich’s life plan

consists in wholehearted participation in the social framework of das Man.

Ivan regards his duty in marriage as leading “a decorous life approved by

society”. (p. 110) He decorates his new home with “all the things people of

a certain class have in order to resemble other people of that class”. (p.

116) Indeed, his house ends up looking like “…what is usually seen in the

houses of people of moderate means who want to appear rich, and therefore

succeed only in resembling others like themselves….” (Ibid) And, “…just as

his drawing-room resembled all other drawing-rooms so did his enjoyable

little parties resemble all other such parties.” (p. 118)

Even Ivan’s attitude toward

death before his accident had been just like the attitudes of those friends

and family from whom he is now so alienated.

The

syllogism he had learned from Kiezewetter’s Logic: ‘Caius is a man, men are

mortal, therefore Caius is mortal,’ had always seemed to him correct as

applied to Caius, but certainly not as applied to himself. That Caius – man

in the abstract – was mortal, was perfectly correct, but he was not Caius,

not an abstract man, but a creature quite, quite separate from all others….I

and all my friends felt that our case was quite different from that of Caius.

(pp. 131-132)

As Ivan grows closer to

death, Tolstoy’s descriptions of the indifference and self-concern of others

begins to focus on Ivan’s family. “…the whole interest he had for other

people was whether he would soon vacate his place, and at last release the

living from the discomfort caused by his presence….” (pp. 134-135) But the

family scenes also serve as a thematic transition. No longer is the

narrative focus solely on the indifference of others, the unpleasantness of

which reaches a kind of climax on the night the family attends the theatre

without him. Rather, Tolstoy shifts his attention from an external

description to a deeper penetration of the contents of Ivan’s mind. The

indifference of other people brings Ivan to an understanding of and a sort

of meditation about his solitude in his death.

After a description of how

his wife and friends react to his pain and irritability without sympathy:

“And he had to live thus all alone on the brink of an abyss, with no one who

understood or pitied him.” (p. 127) And later, Ivan ruminating: “ ‘And none

of them know or wish to know it, and they have no pity for me….It’s all the

same to them, but they will die too! Fools, I first and they later, but it

will be the same for them.’” (p. 130) (Note the implication that we are all

the same in our uniqueness in dying.) When his wife comes to his room, “

‘She won’t understand,’ he thought….And in truth she did not understand.”

(p. 131)

Ivan’s solitude is the

reflection of the inability of his associates to understand the experience

of his death (The misunderstanding according to Heidegger’s analysis

consists in treating death as an inner-worldly event instead of the

world-ending limit that death in fact is). Heidegger would develop his

phenomenological description of other people’s attitudes toward a dying man

by asserting that a person’s being towards death is his alone. It cannot be

related to anything else. (Der Tod als Ende des Daseins ist die eigenste,

unbezügliche….” p. 258) Tolstoy’s summation draws a similar conclusion:

…that loneliness in which he

found himself as he lay facing the back of the sofa, a loneliness in the

midst of a populous town and surrounded by numerous acquaintances and

relations but that yet could not have been more complete anywhere – either

at the bottom of the sea or under the earth….(p. 149)

There is much more, as we

shall see, to Tolstoy’s death narrative than the depiction of the

incomprehension of other people and the subsequent isolation of the dying

individual. But it is worthwhile to take a closer look at this point at what

Heidegger says and Tolstoy depicts.

The common or garden attitude

to death is bad news as far as both Heidegger and Tolstoy are concerned.

Tolstoy says hardly a word of disapprobation regarding these reactions to a

colleague’s death (One might make a case for the use of “so-called”). The

only rhetorical device Tolstoy employs to even hint that there may be a

problem is that he does take the trouble to point out these reactions, and

indeed to give them pride of place in the limited space of his short

narrative. But, unless my intuitions are wrong, we are meant to regard them

as unseemly. The reader is encouraged to view these men’s thoughts as

inappropriate and indeed to view his own past actions in the same way if he

ever behaved or thought in a like manner. Understood as straight social

criticism, Tolstoy’s attitude avoids paradox. If his intent were to

criticize a certain sort of person, a certain stratum of society or even

everyone to the extent that everyone tends to react in the same way as

Ivan’s colleagues, then an inner-worldly solution would suggest itself, i.e.

some sort of death sensitivity training. But his criticism, as long as it is

not explicitly stated, requires that we already understand what the

appropriate reaction to someone else’s death should be, that we know

beforehand that sympathy is better than self-interest. If Tolstoy meant

something that we did not already understand, he would have had to have

stated out loud that he disapproved. If, for example, Tolstoy thought it was

unseemly that these men did not pat their heads and rub their stomachs when

they heard of Ivan’s death, he would have had to actually say, “I think it

is horrible that his colleagues did not pat their heads and rub their

stomachs as soon as they heard the news.” Otherwise, the thought would never

have occurred to us. As it is, Tolstoy must assume a general knowledge, or

at least a knowledge on the part of any reader who wishes to understand his

story, that the behavior he describes is inappropriate, and also a knowledge

that there are alternative, more appropriate forms of behavior. Still the

unsympathetic reactions of Ivan’s colleagues are not bad because they are

universal. They are bad and they also happen to be universal. If, as a

result of Tolstoy’s art, good attitudes were to become universal, there

would be no paradox and no room for disapproval.

As long as Tolstoy sticks to

a polemic against certain sorts of people or against certain inclinations in

all or most people, he does not involve himself in philosophical

difficulties - even though the actual description of Ivan’s aloneness as his

death approaches may have been novel and not necessarily analogous to any

generally held feeling or idea about death. It is meant to give us a new way

of conceptualizing our instinctive fear of death and to give additional

content to the appropriate sympathy we feel for the dying man. Still,

sympathy and aloneness do not cohabit peacefully. Only Gerasim and Ivan’s

son manage to pierce the titanium bound solitude of the individual.

Heidegger (who, like Tolstoy,

does not come right out and say Alltäglichkeit is something he

doesn’t like, but uses descriptive terms that are part of our thesaurus of

disapproval) does involve himself in philosophical conundrums, however, and

not much in Tolstoy’s novella can help him out of them. For his point is

that the inappropriate behavior is constitutive of a structure of commonly

held beliefs and attitudes. When “they” say, feel or do something, that

something is bad because it is universal (viz. performed or felt in common)

and it is universal because it is bad. You can’t have one without the other.

But the very fact that we can understand that a certain type of behavior is

inappropriate, the fact that we can understand that those Russian

gentlemen’s Gerede abut Ivan’s death is unseemly, assumes that our

appropriate sympathetic understanding is also commonly held. If we

understand that Heidegger’s description of Alltäglichkeit implies

disapproval, without his explicitly stating that it should, then, since our

understanding arises from some thesaurus of commonly held beliefs and

attitudes, our understanding is also part of Alltäglichkeit and so to

be despised etc. Our intuitive knowledge that das Man is a real

stinker is itself part of das Man. So I guess we’re all doomed to

mediocrity any way you look at it.

The problems start if we

accept that “anyone” would disapprove of Praskovya Fëderovna’s behavior,

given Tolstoy’s description or Heidegger’s comment. If everybody disapproves

of Praskovya Fëderovna (including, if she read the story, Praskovya

herself), then isn’t this disapproval a phenomenon of das Man, since

it is in fact a feeling that anyone would have? Isn’t it Gerede and a

symptom of Alltäglichkeit? We need at the very least a clarifying

disavowal of the connection if Gerede is what “one” believes. Indeed

if Heidegger wants his philosophical description to be accepted by his

reader, and if an essential characteristic of das Man is that he

holds universally accepted opinions, then isn’t Heidegger actively promoting

that his conclusions become a part of Gerede?

Tolstoy is in a similar

position by writing his story, but he doesn’t get entangled in the paradoxes

that bedevil Heidegger. For one surmises that Tolstoy is preaching and not

philosophizing. He is looking for converts. It wouldn’t bother him at all if

everybody (or at least every Russian) viewed Praskovya Fëderovna’s behavior

in the same way he does and resolved to change their behavior accordingly.

There is a sense in Tolstoy that those evils can be corrected by a sort of

love for one’s fellow man (See below). But the concept of unassailable

isolation in the experience of death is distinct from our disapproval of

those who just cannot understand the dying man. The problem of communicating

that isolation is not overcome by the reader simply subscribing to Tolstoy’s

views. The novelist’s very omniscience that he communicates to the reader by

symbolic and stylistic empathy, seems to belie what he is asserting in the

descriptions of Ivan’s aloneness.

Heidegger is making a

philosophical statement (i.e. a phenomenologically valid descriptive

statement) apparently to the effect that something is wrong with a commonly

held attitude, any commonly held attitude, even if that commonly held

attitude results from an acceptance of his philosophical description of

commonly held attitudes. There are two aspects to this. First, it is

operationally self-defeating. If a claim is made that something believed by

“everyone” is therefore despicable, then the more people who agree with that

claim the closer it comes to being a despicable claim. If you substitute

“false” for “despicable” you end up with something like an Eleatic paradox.

Secondly, it is philosophical. That is, Heidegger aspires to a more

stringent degree of provability than if he were, say, preaching to us from a

street corner. So the philosophical, or even phenomenological demonstration

of his analysis of the alltäglich attitude towards death requires

more than our just nodding our heads in sage agreement. Some sort of proof

is necessary to distinguish Heidegger’s writing from edifying discourse,

though whatever proof he offers need not conform to existing models. (In

later passages, Heidegger argues that the world-ending possibility of death

cannot be grasped by normal conceptual thinking. He does avoid or try to

avoid a different universalizing paradox with that assertion, but he does

not address the operationally self-defeating paradox I just outlined. It

does not do to defend oneself against the paradoxes that arise with

universalizing assertions by just rejecting “logical thinking,” a temptation

against which Heidegger was not entirely immune. For what goes under the

label “logical thinking” is often no more than “making sense.” To simply

reject out of hand without an answer valid objections to one’s philosophical

position, is to risk turning one’s claims into something that nobody else can

understand. If one were to aspire to some sort of different mode of

communication, some sort of symbolic language, then perhaps one is not a

philosopher at all, but a prophet (Interestingly, no less a univocalist than

Locke

falls into this position when we realize that the theory of ideas itself is

the result of personal revelation).)

There are two aspects to

Tolstoy’s story that are not covered in Heidegger’s note or in the analysis

to which the note is appended. The first is that Ivan has a sort of

revelation after his understanding of his death-bound solitude, and that

revelation largely mitigates the anguish of dying and isolation. The

revelation that occurs when Ivan touches his son’s head is religious in

nature. He understands that he had not lived his life correctly, but that he

can now rectify past wrongs by bringing no more pain to other people (He

obviously doesn’t have a lot of time left to act on this resolve). Terms

like “revelation” and “He whose understanding mattered” are borrowed from

the vocabulary of religion. When he comes to his realization, Ivan sees a

light at the end of the tunnel and he ceases to feel both his fear of death

and the physical pains from his illness. “…there was no death,” Tolstoy

asserts (p. 155) presumably because Ivan would soon be up in heaven playing

his harp (To be fair, Tolstoy did not believe in an afterlife, nor in the

historical truth of the Bible. The religious experience he depicts seems to

be a revelation of the moral truths expressed in certain passages of the New

Testament. Nevertheless the experience is a religious experience or very

much like a religious experience.).

This sort of deathbed

revelation was a specialty of Tolstoy’s. Vasili Andreeivich in

Master and Man experiences the same

sort of thing and moreover he is in a position to do something about it by

saving the life of his retainer, Nikita. And, of course, Levin in Anna

Karenina reaches conclusions similar to Ivan’s revelation through a sort

of semi-rational meditation at least partly motivated by Anna’s suicide.

Heidegger did not propose any

prescriptive solutions to the isolation attendant upon dying (at least in

Sein und Zeit), which he in fact describes as an incontrovertible

constitutive category of human existence (If isolation and anguish are

constitutive, then one could conclude that there wasn’t much Ivan could have

done about it). He doesn’t say, “Just be nice to other people and everything

will be all right.” But he does borrow extensively from religious sources

like Tolstoy and Kierkegaard, which leads many to believe that he would at

least have been sympathetic to religious prescriptions.

An understanding of the

second aspect requires some preparation. Elements from

Freud’s

conceptual scheme might help us. Freud argued that certain types of

experience and behavior occurred or were performed for the purpose of

inducing pleasure in the person having the experience or performing the

behavior. The type of pleasure had to do with realizing some goal or

indulging in some distinct experience whose realization or indulgence had at

some time been denied to that person. These phenomena realize that person’s

wish. Dreams, unintentional bits of waking behavior and witticisms and humor

are or are related to wish fulfillment. Freud tends to exempt literature (Gradiva)

but not visual art (Leonardo) from those activities motivated by wish

fulfillment or symptomatic of a wish denied. However, certain works of

literature exhibit characteristics that are notably similar to the wish

fulfillment character of dreams, for example. In some genres such as the

lyric and the ode, the mechanism of the wish fulfillment and the identity of

the wish are so overt that the criterion Freud applies to dreams etc. is not

met – the criterion that the wish be repressed and therefore not consciously

expressed. But some works, especially from the late 19th century,

do meet this criterion and so could be called an exercise in wish

fulfillment analogous to the dreaming of the dreamer.

Based on an inductive

generalization from observations of his patients, Freud maintained that all

dreams had a common element, viz. that the core wish was sexual in nature

and that it related to the attainment of some pleasure forbidden since

childhood. However, Freud may not have made the same generalization about

witticisms and dirty jokes in which the forbidden pleasure was much more

contemporaneous to the participants. So, on this basis, it is possible to

employ elements of the mechanism of wish fulfillment in analyzing a work of

literature without thereby necessarily asserting (or denying) that all

literature is wish fulfillment or that the hidden wish behind every work of

literature involves a childhood sexual fantasy.

Writers whose work functioned

at least partly as wish fulfillment seemed to place in their work a

quasi-anagrammatic code of symbols, allusions and equivocal scenes and

events as if to challenge the reader to tease out their meaning. Tolstoy

employed this technique, particularly in his later stories. The wish he felt

but would not express was a homosexual fantasy. To see this, we need to

locate and translate the elements of the anagram.

The key scene in Tolstoy’s

homosexual subtext is the relief Ivan obtains from placing his ankles on the

shoulders of the young servant, Gerasim, and the central symbol in the

fantasy is the image of Ivan feeling pleasure in this otherwise awkward

position. The scene begins (pp. 136 ff.) with Ivan asking Gerasim to raise

his legs and place them on a chair because “It is easier for me when my feet

are raised.” But it turns out that no inanimate support can lift Ivan’s legs

high enough. In fact the crucial factor in providing Ivan comfort is not how

high his legs are raised but the fact that Gerasim is supporting the ankles.

“It seemed to Ivan Ilyich that he felt better while Gerasim was holding up

his legs…. in that position he did not feel any pain at all.” The leg

holding ritual became habitual. “After that Ivan Ilyich would sometimes call

Gerasim and get him to hold his legs on his shoulders, and he liked talking

to him.” Gerasim’s support turns into an emotional relationship and it lasts

the entire night. “He saw that no one felt for him, because no one even

wished to grasp his position. Only Gerasim recognized it and pitied him. And

so Ivan Ilyich felt at ease with him. He felt comforted when Gerasim

supported his legs (sometimes all night long) and refused to go to bed….” It

is interesting that Gerasim is an exception to the general inability of

other people to understand the experience of Ivan’s dying. His role in the

story parallels that of Ivan’s son. The two characters might be a split

rendition of a single fantasy character in a sort of centrifugal version of

Galton-style merging. The leg lifting sequence concludes with a scene where

Ivan sends his wife away so that he can remain alone with Gerasim.

The arrangement of an

individual lying on his back while his legs are supported on the shoulders

of another is awkward in itself (One would think some sort of inanimate

contraption could have been devised to maintain Ivan’s ankles at the proper

height. Obviously Gerasim’s presence is at least partially responsible for

Ivan’s comfort) and awkward in its narrative function. The situation is

clarified when we understand that the two men are in a coital position.

Gerasim is playing the male role and Ivan, on his back, the female role. The

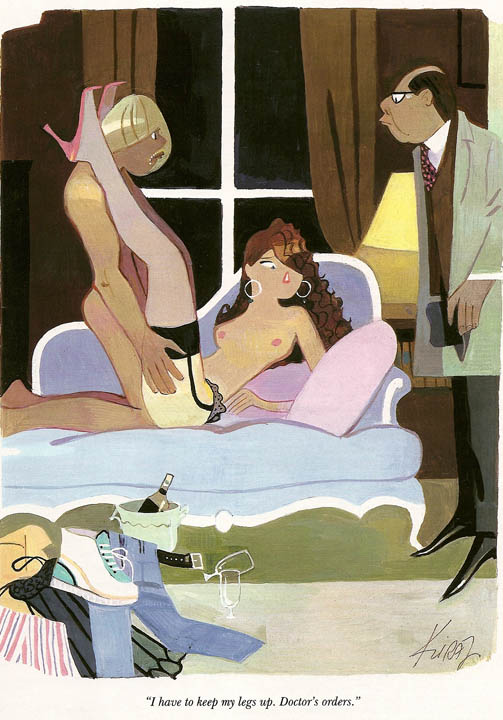

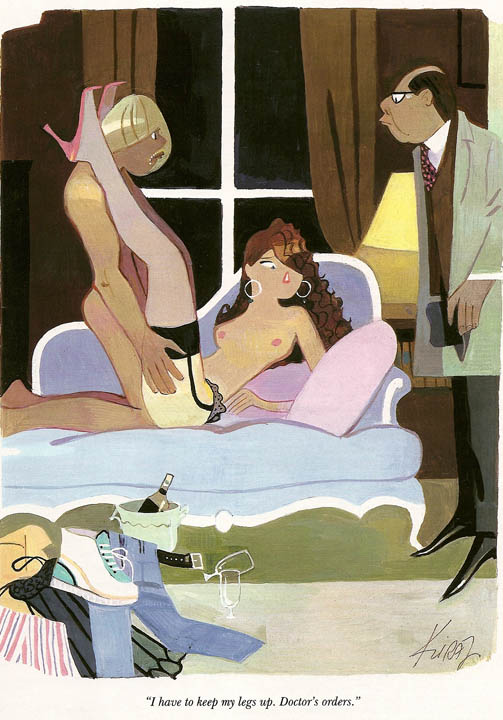

sexual nature of the arrangement is such that the following cartoon would be

incomprehensible without our understanding that the position is indeed

coital:

Perhaps the position is also

conducive to anal penetration such as might be favored in male-male fucking.

Tolstoy associates the arrangement with anal satisfaction by introducing the

leg-lifting scene with a description of how Gerasim helps Ivan defacate (p.

135. Tolstoy calls Ivan’s shit “the things”).

The central symbol in

Tolstoy’s underlying fantasy is an anal erotic coupling. Tolstoy leaves a

trail of hints that this is undoubtedly homosexual eroticism. The first is

the sexual enthusiasm with which he describes Gerasim’s face and physique.

He is described as a “Clean fresh peasant lad” with “strong bare young

arms,” the “first downy signs of a beard” and “glistening white teeth.”

Compare this with the descriptions of Praskovya Fëderova, Ivan’s official

love partner, that go from that go from “…a sweet, pretty and thoroughly

correct young woman….” (p. 109) and “…the most attractive, clever and

brilliant girl of the set in which he moves….” (p. 108) to “…a short, fat

woman who despite all efforts to the contrary had continued to broaden

steadily from the shoulders downwards….” (p. 99) “His marriage, a mere

accident, then the disenchantment that followed it, his wife’s bad breath

and sensuality and hypocrisy….” (p.148)

Indeed Tolstoy’s misogyny,

which gets pretty much out of control in later works such as The Kreutzer

Sonata, and burbles along as a subtext as early as Anna Karenina,

where Tolstoy appears to take sadistic pleasure in the breakdown and

eventual physical destruction of Anna, as well as his autobiographical

hostility toward his wife, is also a displacement of the underlying

homosexual desire (Misogyny, as had already been popularized by Schopenhauer

and Strindberg, was not always associated with homosexual wish fulfillment.

Tolstoy put the popular theme to that use). The bad behavior and physical

repulsiveness of women contrasts with yearning though offhand remarks about

handsome men (Tolstoy demonstrates a high degree of enthusiasm for the

buttocks of Vronsky and his comrades in their tight uniforms). Just as

Levin’s conversion mirrors Ivan’s revelation, so the hostility to Anna

mirrors the hostility to Praskovya Fëderovna. The significant difference

between the early and the later works is the presence in early texts of

positive female figures like Kitty. But even these women represent a

conscious wish fulfillment for a successful spouse and marriage (Masha in

Family Happiness may also symbolize a

fantasy of sexual relations with a daughter.)

Another occasion Tolstoy uses

to transfer his perhaps unconscious homosexual fantasy into a substitute

image is the narrative surrounding Ivan’s decoration of the family’s new

house. Ivan assumes the female role in appropriating a task normally

undertaken by the wife. His wife and daughter are reduced to the role of

admiring spectators once the decorating has been finished. Moreover, the

critical scene of Ivan’s fatal accident while decorating now assumes

additional meaning when viewed as a symbol of sexual penetration. And,

because it occurs during the female activity of decorating, it can be

regarded as homosexual penetration. (One could go a step further and opine

that the “queer taste” in Ivan’s mouth after the accident has overtones of

fellatio.) The significance of the accident with the window knob as both the

physical cause of Ivan’s death and a symbol or substitute of homosexual

penetration provides a point of contact between the explicit (isolation in

death) and latent (homosexual fantasy) content of Tolstoy’s story. Freud

quite often points out that neurotics exhibit a surprising intensity in

their symptoms, which on the surface are occasioned by trivial occurrences.

In The Death of Ivan Ilyich, however, such a disproportionate

reaction is unnecessary. The strength of the emotions surrounding death are

more than a match for the very powerful sexual drive and the repressed

fantasies occasioned by the sexual drive. The intensity of Ivan’s emotions

could only be credible with a credible motive, and of course the fear of

death is a credible motive. But the fear of death is at the same time a

substitute “symptom” masking a perhaps equally powerful sexual impulse.

Once the homosexual subtext

in The Death of Ivan Ilyich is recognized, an otherwise mysterious

passage in Tolstoy’s description of Ivan’s school days is perfectly clear:

At school he had done things

which had formerly seemed to him very horrid and made him feel disgusted

with himself when he did them; but when later on he saw that such actions

were done by people of good position and that they did not regard them as

wrong, he was able not exactly to regard them as right, but to forget about

them entirely or not be at all troubled at remembering them. (p. 105)

Tolstoy takes trouble to

establish that the horrid things were not extramarital heterosexual sex or

sex with prostitutes because he records Ivan’s engagement in that kind of

sex without circumlocution (p. 106). The alternative that suggests itself

most directly is homosexual sex.

Another scene with notable

homosexual symbolism occurs in Master and Man. Just as in The

Death of Ivan Ilyich the hero of the story assumes a fantasy coital

position with another man. This time Tolstoy depicts an easily recognizable

missionary position, lingering over the description of the contact of the

two bodies.

…he hurriedly undid his girdle, opened

out his fur coat, and having pushed Nikita down, lay down on top of him,

covering him not only with his fur coat but with the whole of his body,

which glowed with warmth. After pushing the skirts of his coat between

Nikita and the sides of the sledge, and holding down its hem with his knees,

Vasili Andreevich lay like that face down, with his head pressed against the

front of the sledge. Here he no longer heard the horse’s movements or the

whistling of the wind, but only Nikita’s breathing.

…tears came to his eyes and his lower

jaw began to quiver rapidly….(His) weakness was not only not unpleasant, but

gave him a peculiar joy such as he had never felt before….He remained silent

and lay like that for a long time….he could not bring himself to leave

Nikita and disturb even for a moment the joyous condition he was in. (pp.

288-289)

As with Ivan Ilyich, the sexual imagery merges with

religious imagery, and, as with the other story, the identification of the

two sorts of experience follows a pattern Freud diagnosed in his treatment

of neurosis and his analysis of dreams. The religious tone is an overlay and

a disguise for Tolstoy’s repressed and inadmissible homoerotic fantasy. But

equally the association of sexual desire and activity with the fear and

experience of death overdetermines the significance of the scene. Vasili

Andreevich’s act embodies both sexuality and, to use a Heideggerian phrase,

Sein zum Tode, and it is a phenomenon not unworthy of examination

that these two equally strong states of mind could so merge as to be

expressed by one image:

Then suddenly his joy was completed. He

whom he was expecting came….it was he whom he had been waiting for. He came

and called him; and it was he who had called him and told him to lie down on

Nikita. And Vasili Andreevich was glad that one had come for him. ‘I’m

coming!’ he cried joyfully, and that cry awoke him, but woke him up not at

all the same person he had been when he fell asleep. He tried to get up but

could not, tried to move his arm and could not, to move his leg and also

could not, to turn his head and could not….He understood that this was

death….and it seemed to him that he was Nikita and Nikita was he, and that

his life was not in himself but in Nikita….And again he heard the voice of

the one who had called him before. ‘I’m coming! Coming!’ he responded

gladly, and his whole being was filled with joyful emotion….After that

Vasili Andreevich neither saw, heard, nor felt anything more in this world.

(pp. 290-291)

It is worth noting that the

conclusion of Master and Man echoes the rather bizarre conclusion of

Flaubert’s La Légende de Saint Julien l’Hospitalier, published nine

years earlier and which Tolstoy had very likely read. While clearly

homoerotic, Flaubert’s tale does not exhibit the same kind of overt

fulfillment of a repressed wish as Tolstoy’s. While Tolstoy adapts

Flaubert’s brilliant synthesis of physical revulsion (the drunken peasant is

a somewhat milder version of Flaubert’s scrofulous vagrant) and

sexual/religious ecstasy, his concerns are different. Julien’s taste for

unrestrained bloodletting is punished in the accidental murder of his

parents that leads to his attempt at expiation as a ferryman. This story has

the indeterminacy of a genuine fairy tale and it is capped by the joyful

blasphemy of Julien’s sex scene with Jesus. And both tales stir distant

recollections of the hilarious lesbian seduction scene from Diderot’s La

Religieuse.

It is the overdetermination

in Tolstoy’s literary imagery that provides a point of contact between

Heidegger’s philosophy, wherein no mention is made of sexual matters or of

anything relating to the pleasure principle, and the findings of Freud (and

indeed the mechanistic, pleasure-based psychology of

Descartes).

In spite of their temporal and geographical proximity both Freud and

Heidegger wrote as if the other didn’t exist. Indeed Heidegger’s entire

conceptual structure is remarkably sexless. But Freud’s complex psychology

does admit that the drives relating to sexuality and the drives and emotions

relating to dying somehow work in tandem. Where you find the one the other

is somewhere lurking. Freudian concepts such as overdetermination and

Verdichtung help us understand how contrasting emotions can interact.

Since Heidegger was more directly inspired by Tolstoy (and writers with

similar concerns, like Kierkegaard), the sexual element in Tolstoy’s work

might help a bit in understanding whether sexuality plays any role in

Heidegger’s existential phenomenology.

The basic idea we can pick up

from Freud is that works of literature can function analogously to the

symptoms of hysteria. That is they create a means of acting out through

symbolic representation a disturbance, which, in the hysteric’s case, is the

cause of his illness. Viewed this way, at least some works of literature are

symptoms and not the original fantasy. The important difference is that they

show signs of the original fantasy having been repressed and so turn to

techniques of disguise and displacement to allow the individual to relive

his fantasy without trauma. In an essay entitled

Hysterische Phantasien und Ihre Beziehung zur

Bisexualität that is relevant not only because of its

reference to bisexuality but also because it appeared at a time (1908) when

he was beginning to focus on literature as a sort of fantasy, Freud proposes

a number of formulas for the identification of symptoms of hysteria. The

Death of Ivan Ilyich exemplifies at the very least three of those

formulas (The others mostly have to do with childhood experiences not

expressed in the story). Formula 4 states that the hysterical symptom is the

realization of one of the unconscious fantasies that serve to fulfill a

wish. Formula 7 states that the hysterical symptom functions as a compromise

between the drive to express and the opposing drive to repress a sexual

fantasy. Formula 9 states that a significant number if not all underlying

fantasies are combinations of heterosexual and homosexual desires.

Conformity to these formulas

suggests that Tolstoy at some point in his life began to experience

homoerotic desires (Nothing, or almost nothing, in Tolstoy’s biography

betrays much interest in actual homosexual encounters. A little anecdotal

evidence can be found in

Wilson, pp.86, 87, 89, 91, 131, 197, 345,

353 and 494. At a conscious level Tolstoy defended his infatuations as

Platonic and asserted that they were unrelated to “coitus.”). Because those

desires were forbidden both in Tolstoy’s mind and by the society he lived

in, he repressed them. Repressed desires do not just go away, however, and

literature became a means of surreptitiously reliving a homosexual fantasy.

Fantasies of fucking male servants were sufficiently distorted such that

they appeared to arise from other causes. Likewise the physical contact with

the male was innocently generated by events in a way that gave it a sort of

natural necessity and made it incidental to the overt action. Ivan needed

Gerasim between his legs to relieve his pain, but in the narrative he

obviously did not become ill so that he could touch Gerasim’s penis with his

butt hole. Vasili Andreevich needed to save Nikita’s life and that was why

in the story he embraced the servant.

There are three other

elements that Tolstoy brings together in these stories with the theme of

homoerotic coupling. They are religion or religious experience, death or the

fear of death, and the isolation of the individual. Freud deals with the

first two and also obviously with sexuality. Heidegger deals extensively in

Sein und Zeit with the latter two and does not mention sexuality of

any kind.

During the same period around

1908 that Freud began to turn to literature, he also saw associations

between strong religious experiences and strong sexual feelings. Ultimately

he found them to be the same emotion. An entertaining example of the

identity appears in his essay on Jensen’s Gradiva (Der

Wahn und die Träume in W. Jensen’s ‘Gradiva’), where he

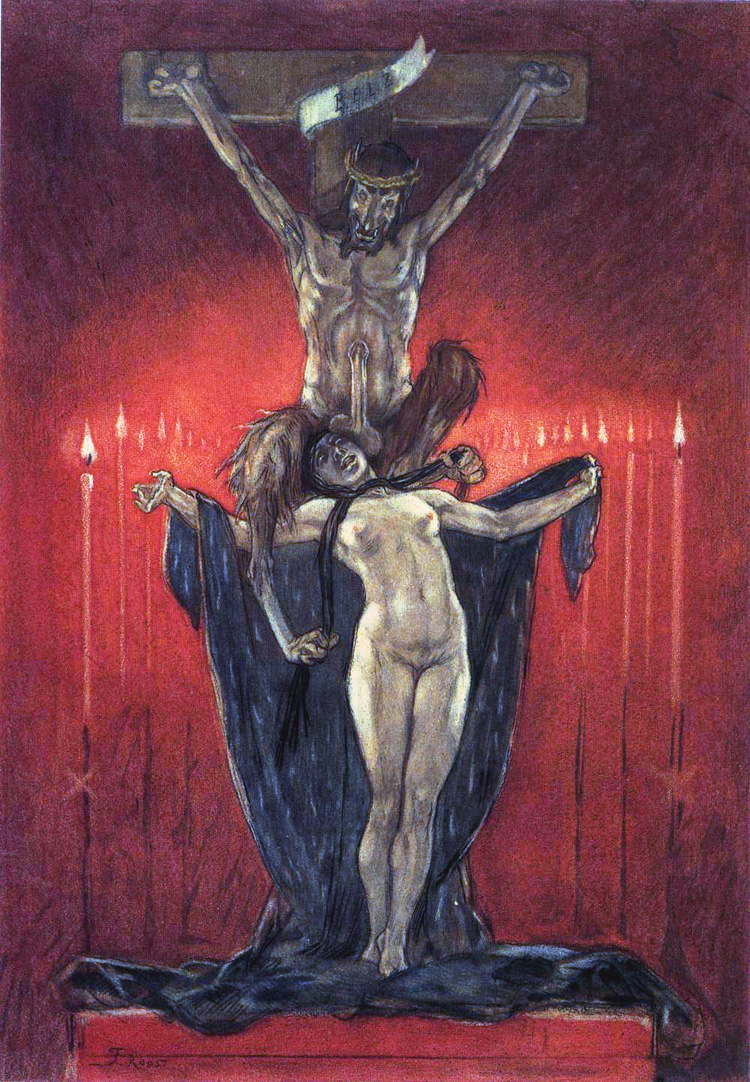

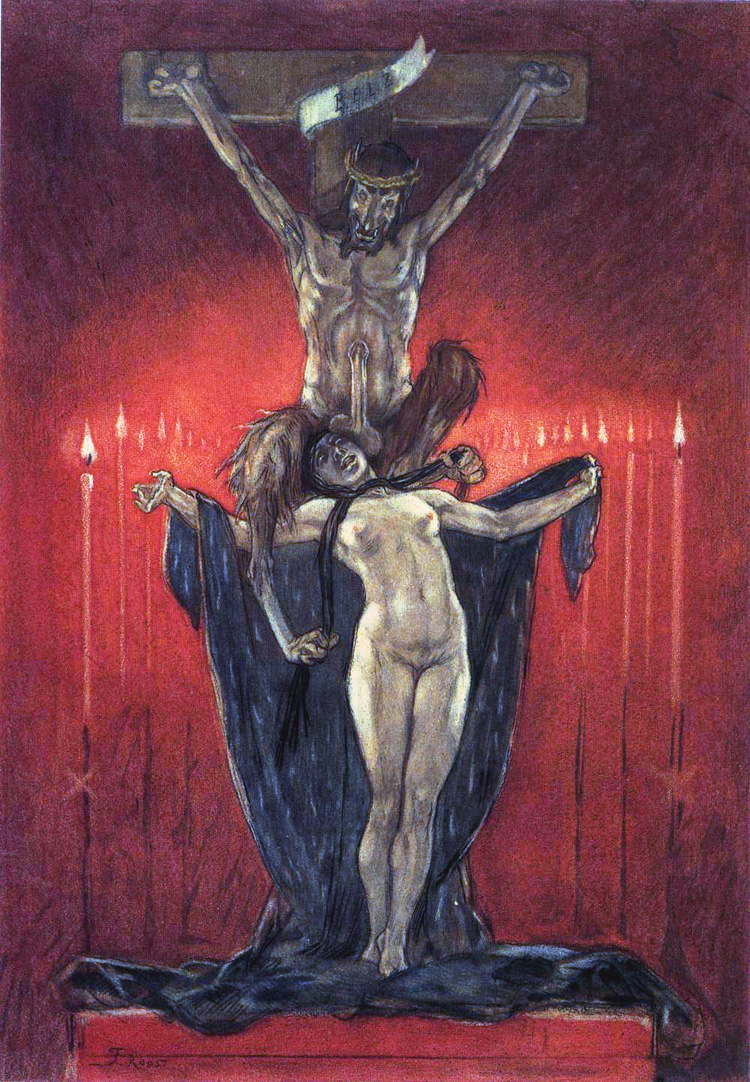

describes an etching by Félicien Rops that depicts a monk in ecstasy before

a crucifixion image replacing Jesus with a sexy nude woman:

Cf. also:

(I might add that Spanish

truck drivers to this day display nude pinups alongside pictures of the

Virgin Mary in their cabs.)

Religious behavior is in fact

a manifestation of the same psychological complex that exhibits itself as

compulsion neurosis. So our overall conceptual scheme includes the

following: Repression of sexual feelings is the originating event. Fantasy,

sometimes allied with other neurotic symptoms is a manifestation of this

sexual feeling trying to break through. Literature acts as a kind of

fantasy; religious behavior is a form of neurosis. Thus it is no surprise

that Tolstoy should choose to disguise his homosexual fantasy as a religious

revelation. The sexual element also contributes to the intensity of the

feeling of Tolstoy’s characters when they experience their spiritual

conversion. The spirituality is a veil; the substance is the homoeroticism.

Just as religious emotions

have their source in sexual emotions (They are a perversion of the original

sexual feeling), so repressed homoerotic desires are a source of neurosis.

They can also be sublimated and find expression in “higher” cultural

products, such as works of literature. Freud said it best:

Die für die Kulturarbeit verwertbaren

Kräfte werden so zum grossen Teile durch die Unterdrückung der sogenannt

perversen Anteile der Sexualerregung gewonnen….Die Konstitution der von

der Inversion Betroffenen, der Homosexuellen, zeichnet sich sogar häufig

durch eine besondere Eignung des Sexualtriebes zu kulturellen Sublimieurung

aus. (Die

kulturelle Sexualmoral und die moderne Nervosität, VII pp.

151 and 152-153)

The final element in

Tolstoy’s story is death, the fear of death and the individual’s isolation

as made evident to him when he dies. Heidegger relates that fear to the

isolation constitutive (in Heidegger’s view) of human existence. Fear of

death is a powerful and genuine emotion on its own, perhaps one of the few

emotions strong enough to serve as a disguise for the turbulent emotions

surrounding the re-emergence of a shame-filled and repressed sexual drive.

It is obviously not the only emotion Tolstoy used as an ersatz. Misogyny in

The Kreutzer Sonata and obsessive greed

in Master and Man may have played a similar substitutive role. But

the peculiar appropriateness of Ivan’s fear of death as an ersatz seems to

show something more about both emotions. We feel that there is a sexual

element in our fear of death. Equally there seems to be an intimation of

death in sexual desire or the repression of sexual desire. The intimation of

involvement between sexuality and death is manifested in the term frequently

used by both Freud and Heidegger, not “fear” or “Furcht,” but “Angst”

or “anxiety,” a term both define as objectless fear or fear of nothing. It

is not entirely appropriate to observe that Freud and Heidegger might not

mean the same thing by “anxiety,” since both (Heidegger rather more than

Freud) are given to personalized definitions of the terms they use. For not

only do they use the same term, they define it in the same way (Note that

Freud, VII pp. 261 ff., defines anxiety as objectless fear, which, without

the logical sleight of hand, is tantamount to Heidegger’s fear of nothing.

This shouldn’t be a surprise since objectless fear is pretty much the common

language meaning of anxiety.). Moreover, the choice of a term from common

usage implies that the way the term is commonly understood has some bearing

on what they mean, however specialized their uses may be. If not, he would

have to invent a complete neologism. When Heidegger chooses a common

language term for specialized use, he must intend to anchor our

understanding of his use in our understanding of the common language term.

The philosophical use he makes of “anxiety” must be related to what we

recognize as personal feelings of anxiety or as symptoms of anxiety in

others.

Heidegger’s philosophical

treatment gives anxiety a sort of categorical status. Just as human

existence is at least partly defined as completely particularized, utterly

divorced from commonality with others, so anxiety is an emotional

understanding on the part of the isolated individual of this sort of

isolation, which makes him human. An individual’s death is also related to

his isolation because no one can die someone else’s death. Using a kind of

metaphysical wordplay, Heidegger makes anxiety the link between isolation

and death. The anxiety the individual feels and which is a manifestation of

his individuality, is in fact a fear of his death. The wordplay enters in

because his death is the nothingness of the individual. So when he fears

death he fears his non-existence. Since the world outside the individual has

a sort of relation of dependence on the individual, the non-existence of the

individual implies a generalized kind of nothingness. For this reason the

fear of death is the fear of nothing or anxiety. So anxiety is equally a

manifestation of the insurmountable particularity of the individual. The

justification of Heidegger’s categorical description is not an issue here,

although his citation of The Death of Ivan Ilyich is meant to work as

a kind of argument in its favor. If you understand (emotionally) Ivan’s

feelings about death, you also understand on a more conceptual level

Heidegger’s categorical scheme.

That anxiety should in fact

and perhaps also categorically express sexual feelings is an idea Heidegger

never discusses, although Freud’s theories were practically part of the

intellectual canon by the time (1928) of the publication of Sein und Zeit.

(A perverse imp might opine that Heidegger tried to “rescue” anxiety from

the clutches of sexuality; if so, he failed miserably.) But Freud’s

findings about anxiety, and particularly about anxiety dreams or fantasies,

fills in the psychological (if not categorical) picture of this emotion. In

his essay on Gradiva Freud asserts the lineage between anxiety and

sexual feelings in anxiety dreams:

Die Angst des Angsttraumes entspreche

einem sexuelle Affekt, einer libidinösen Empfindung, wie überhaupt jede

nervöse Angst, und sei durch den Prozess der Verdrängung aus der Libido

hervorgegangen. (VII, p.87)

Anxiety in a dream and in a

neurosis is the emotional manifestation of repressed erotic feelings. Freud

makes this point in numerous loci; the particular value of this passage is

that it comes in the context of the interpretation of a novella, a work of

literature. In this case Freud concentrates on the anxiety dreams of a

character within the story, treating, interestingly enough, the story itself

not as a work of fantasy and so symptomatic of Jensen’s psyche, but as

something more equivalent to a psychoanalytic case study, where another

character, Zoe, plays the role of the psychoanalyst. But in several other

passages he views literary works as often on the same footing as day dreams,

dreams and other fantasies in that they all involve wish fulfillment on the

part of the creator of the fantasy. Equally one might opine that, just as

there are anxiety dreams, much literature could also be viewed as anxiety

fantasy.

The anxiety in an anxiety

dream, according to Freud, is not the real emotion. Rather it is the

substitute manifestation of another negative emotion felt at the resurgence

of a strongly felt sexual desire. This throws light on The Death of Ivan

Ilyich. Ivan’s (and Tolstoy’s) explicit symptom is anxiety over the

imminence of Ivan’s death. However, for Tolstoy the author this story is a

fantasy and his anxiety masks his revulsion against the re-emergence of his

homoerotic feelings. Clues as to the presence of those feelings are strewn

throughout the story, as I showed earlier. The death anxiety serves to lead

the reader (and the author) astray and at least partially distort the true

nature of his strong emotions.

Die so entstandene Angst übe nun – nicht

regelmässig aber häufig – einen auswählenden Einfluss au den Trauminhalt aus

and bringe Vorstellungselemente in den Traum, welche für die bewusste und

misverständliche Auffassung des Traumes zum Angstaffekt passend ercheinen.

(VII, p. 88)

The subjunctivity of the

passage marks a caution that Freud does not really feel. Fantasy anxiety is

not real anxiety but a distortion of other equally powerful negative

feelings like shame and disgust. The value of the overt understanding of

Tolstoy’s story, such as Heidegger prizes, puts some breaks on a strong

Freudian analysis of Tolstoy’s fantasy. The Death of Ivan Ilyich is

most likely multivalent. It is about death anxiety and it is about anxiety

in the face of sexual repression. But the resolution of Ivan’s death anxiety

in a religious vision is at the same time a resolution of Tolstoy’s sexual

repression in the symbolic fucking of Gerasim.

One other point should be

made about the fear of death and its relation to religious belief. That fear

is so strong that it can compel us to assert an obvious untruth, namely that

we do not really die. Religion is an imaginary product of the fear of death.

Freud would eventually develop that theme at length and he already had

notions along these lines in his early psychoanalytic writings:

Ja selbst

der nüchtern und ungläubig Gewordene mag mit Beschämung wahrnehmen, wie

leicht er sich für einen Moment zum Geister glauben zurückwendet, wenn

Ergriffenheit und Ratlosigkeit bei ihm zusammentreffen. (VII, p. 99)

It is amusing to note that,

in arguing that religion is one of the (unsatisfactory because we are

obliged to sacrifice our desires to various Gods) cultural constructs that

results from a sublimation of repressed sexual desires, Freud quotes exactly

the same Biblical passage that Tolstoy makes the epigraph of Anna

Karenina: Vengeance is mine, saith the Lord. (VII p. 139)

By illustrating or

exemplifying so many of the issues raised by Freud and Heidegger, Tolstoy’s

story provides a point of contact between the two most important

psychological theories of the last century. Behaviorism and physicalism are

not, strictly speaking, theories, but rather frameworks for theories or

conditions on theories. There are, of course, psychological theories that

satisfy behaviorist or physicalist conditions. Likewise, Heidegger considers

his concepts in Sein und Zeit not as constitutive of a psychological

theory, but rather as a categorical, or rather category-like (existential)

structure for the phenomenon of human existence. He may be justified in that

he proposes his existentials in the context of a conceptualization of human

existence that is decidedly not physicalist, but his claim is ambitious to

say the least. In order to demonstrate that the existentials and ancillary

concepts proposed in Sein und Zeit are indeed similar to what we have

come to recognize as categories, one would think that he would have to show

some sort of conceptual or concept-like dependence of psychological

theories, like Freud’s, on the existentials. This would have to be shown as

long as a theory like Freud’s were a properly psychological theory even if

it turned out to be invalid. The relations commonly accepted between

physical concepts and, for example, Aristotelian categories are subsumption

or presupposition. It is, nevertheless, interesting that the same imaginary

cum real event (Ivan’s death and Tolstoy’s fantasy about Ivan’s death) can

illustrate both Freud’s psychological theory and Heidegger’s philosophical

categorization. Heidegger might regard the sexual valence of Tolstoy’s

fantasy as a matter of fact (faktisch) and not on a level of

metaphysical universality (Unlike isolation without which there is no human

existence; take away the sexual valence, Heidegger might argue, and there is

still human existence). However, one element of the appeal of Sein und

Zeit is how it ties together apparent matters of fact with concepts

similar to logical concepts in that they aspire to the same sort of

universality as the Aristotelian categories. In this respect Gerede

is quite similar to sexual repression in that neither is endowed with the

sort of universality claimed for the existentials (Although Heidegger tries

to tie the sort of Gerede exhibited by Ivan’s friends to the

ostensible philosophical misinterpretation of human existence as

exhaustively describable as extended matter).

The final point has to do

with the status of Freud’s interpretations. Of course, they provide a degree

of illumination about the psychological mechanism involved in much art and

literature. In one sense, however, his is not really an understanding coming

from the outside towards the literature of his time. Rather, he and his

contemporaries seem to be saying the same thing. Freud does not so much

understand Tolstoy’s story (metalinguistically, so to speak) as assert in

his scientific language precisely what Tolstoy, consciously or

unconsciously, was expressing symbolically. Jensen was not a patient, but a

co-researcher; and, if Freud had produced the above analysis of The Death

of Ivan Ilyich, the same could be said about Tolstoy. At least as far as

his contemporaries are concerned there is no distinction of levels. Perhaps

Freud was expressing as objective psychoanalytic theory, insights about the

self and about family history that many writers at his time also came to

understand. One might suggest that Freud’s theories do not really constitute

an understanding from an external standpoint of literary works so close to

him in time and culture. Rather his literary peers were in a way making the

same point as he was, as is evidenced by the obviousness of their symbolism

(Melville much more explicitly than Tolstoy; but Melville had fewer qualms

about his homosexuality). Thus Freud wrote within a cultural period that

understood at some semi-conscious level the workings of fantasy symbolism

and the sexual element in fantasy almost as well as he did (Significantly,

this type of self-symbolism enters into Western literature at about the time

the author assumes a role as a kind of character in the work). In fact one

might opine that his insights were sparked partly by the revelation of this

literature (It is an error to deny that at least some literary works can

intentionally make assertions and arguments (in their own way, usually by

the techniques of illustration, exemplification and sympathetic

understanding) just like non-fiction). It is an open question whether the

neurotic symptoms Freud diagnoses are specific to a certain cultural period,

and, more profoundly, whether the structure and system of the mind is

changed by the very fact of understanding Freud’s discoveries. It may be

that the structure of the repression of sexual desires and the mechanism by

which those desires were expressed symbolically in literature, dreams and

daily life, changed once the culture became explicitly aware of Freud’s

theories.

These observations may help

explain why psychoanalytic analyses of literary works can have a flattening

effect (“Is that all that it’s about”). Once the moment of insight

has passed and the mind has absorbed Freud’s analysis, that mind changes. At

the same time one cannot help feeling that writers contemporaneous to Freud

had semi intentionally inserted the meaningful symbols in their work. Indeed

psychoanalytic interpretations do not work nearly so well for artists and

writers more distant in time, such as Leonardo and Shakespeare, simply

because a different structure of the mind at those times makes all

psychologizing interpretations inappropriate.

One consequence is that Freud

does not enjoy the position of external observer in the same way that a

physicist, on a macro level at least, is the external observer of physical

phenomena. Or it may be that psychoanalytic theory, like

Newtonian

and even relativistic mechanics with respect to the physical world, might

mistakenly view the psychic universe as static, where mechanisms like

repression do not have ongoing phylogenetic histories. This is worth

reflecting on; it might help us understand how there can be such a thing as

an objective psychological theory.

There is another Tolstoyan

theme, highlighted in The Death of Ivan Ilyich, that was much shared

by writers and artists of his time, namely the theme of the isolated

individual. Although a version of this idea was developed during the

Renaissance, it reappeared with special profundity and concern in the

culture largely indebted to Rousseau. The concept that the individual was an

object of unique concern led not only to a revival of confessional

literature but turned almost all literature at the time into disguised

confession or autobiographical obsession. Examples include not only Tolstoy,

but Wordsworth, Whitman, Rimbaud, Melville and even on occasion Flaubert and

Dickens. The list could go on and on. Nietzsche’s (Renaissance inspired)

confessional grandiosity is a much more complex case; it is in fact a parody

of self-obsession in literature. The moral and political implications of the

unique position of the isolated individual were drawn by, among others,

Emerson,

Kierkegaard and Stirner. The exemplary insanities of the 19th

century (Van Gogh, Hölderlin, Nietzsche) represented an acting out of the

theme of isolation that in literature was represented on a level of fantasy.

This list also could go on and on. What should be remarked is not that

Tolstoy’s contemporaries and predecessors mined this artistic theme or

mental perspective, but that it is not a concern of all art or philosophy.

The 19th century, so to speak, invented it.

One of the conclusions drawn

from the special status of the isolated individual was that there was

something wrong with established nations and their cultures. Many felt the

need for different sorts of communities. At an extreme, one could conclude

that there was no such thing as an acceptable society. Unlike the theme of

the isolated individual, utopian communitarianism was not novel to the 19th

century; it dates back at least to the Reformation (Hill). But its

association with artists and writers was, on the whole, novel. It is worth

remarking that radical individualism can be subject to a sort of operational

self-contradiction reflected in the self-contradictory statement, “All men

are unique.” Insistence on this operational self-contradiction was to be a

center piece of

Sartre’s philosophy (unsatisfactorily

resolved in the commitment to some sort of engagement, presumably in

the Communist party). The dialectic of uniqueness observes that the artist

in revolt is just like all the other artists in revolt. But not all artists

in revolt did so because they believed themselves to be or aspired to be

completely unlike everyone else, including other artists in revolt. In a way

the constitution of a Bohemia does not fall prey to this dialectic because

the aim of the Bohemian is not to be unique but to establish a different

form of society as an alternative to bourgeois society. At one level

Heidegger may also not fall into this dialectic, the level where his concept

of uniqueness permits sameness in virtue of uniqueness. This is similar to

the problem of numerical identity. Every point in space is the same as every

other point in that it is a point. Still it is numerically and geometrically

distinct from other points, so the identity is not complete. In the same way

the identity of unique individuals is not total, it is only partial in that

they all possess the quality of uniqueness.

The unique individual is, of

course, the Heideggerian theme. Freud largely ignores this concept,

understandably so since it does not fit well with his ambition to provide an

objective theory of the mind, a theory whose very universality asserts that

in the relevant respects all people are the same and not subject to any sort

unqualified uniqueness. Freud, of course, subscribed to the other pole of 19th

century culture, roughly speaking the positivistic pole, the view that all

phenomena, including mental phenomena, could be treated in the same way that

physics had successfully treated force and mass and associated physical

phenomena, namely through measurement and the discovery of lawlike

regularities. No matter that Freud did not subscribe to the physicalist

reduction of mental activities and dispositions. Psychoanalysis is based on

the ambition to devise an objective model for the structure of mind and its

thoughts, actions and dispositions. Since Freud ignored his contemporaries’

assertion of individual uniqueness (while clearly recognizing their other

theme of distorted symbolic representation of repressed sexual wishes), did

he miss something? Does that mean there is something lacking or just wrong

in the psychoanalytic theory of mind? In a wider sense, are we forced to

choose between accepting the radical uniqueness of the individual and the

possibility of an objective science of the human mind? Very possibly this

last question may be an irresolvable antinomy. What is significant may be

that there emerged in the 19th century a conceptual structure

that was defined by the two poles of individualism and positivism. The

interest may lie in understanding that conceptual structure rather than

deciding between the two “camps.”

Looking at this

story from a somewhat different angle, however, we find that Tolstoy is

expressing an important sentiment beyond the apparent and superficial

misogyny and the description of a somewhat belated revelation of irreducible

human individuality on the occasion of dying. For Ivan is thrown (to use a

Heideggerian turn of phrase) into a situation not of his own making and, on

the occasion of his fatal illness, he saw in its true colors as an ugly and

largely arbitrary affair, namely the bourgeois family, or, to be fair to the

bourgeoisie, any family since all family structures represent repulsive and

primitive practices. The family was not an inevitable or even particularly

beneficial life choice for Ivan. Rather he looks up one day and finds

himself saddled with this group of uninspiring strangers, all other

opportunities for a different life closed off and all he illusions of some

sort of special communion between family members shorn away. Tolstoy

chronicles in his history of Ivan’s early life how he happened to get thrown

into his particular mess by the creeping and insidious effect of social

expectations that Ivan had unbeknownst fully internalized (He did after all

decide on his own that it would be something of a lark to get married and

that Praskovya Fëderovna seemed as good a candidate as any for a breeding

partner). Tolstoy was not alone in his insight.

Samuel

Butler, for one, engaged in a searching examination of the harm

done to the child by the family institution – a situation into which his

hero was thrown with little opportunity for personal choice. And Gauguin’s

exemplary rejection of his family and embrace of the opprobrium that

rejection entailed was at least as important a moral exemplar as the various

exemplary insanities that have done so much to entertain us. Nor was Ivan in

any way special or particularly gifted. He was certainly not artistically

inclined. His defining quality seemed to be an easygoing ability to get

along and to perform his duties without causing a ruckus - a personality

perfectly suited for achieving the young Ivan’s superego driven goal of

financial comfort within his own class. The other members of Ivan’s family

could very well have come to the same realization abut their respective

situations, even the cow-like Praskovya Fëderovna, in which case Ivan

himself would assume the role of horrible exemplar of das Man. What

Tolstoy and Heidegger have observed is that there is something particularly

effective about the experience of dying that shows the unfortunate and

arbitrary institution of the family for what it is.

Tolstoy’s

capacity for insight is not unrelated to his homosexuality. Homosexuals seem

to enjoy a privileged perspective from which to observe the evil effects of

primitive institutions like the family. We need only think of Genet, Rimbaud,

Burroughs, not to mention many of the 17th century libertins,

to identify superlative examples of homosexual socially critical literature.

I think there is a plausible explanation for this. Proponents of practices

like family formation almost without exception condemn homosexual sex (and

indeed any sex not solely for the purpose of breeding). That part of the

homosexual’s personality that feels itself under attack is empowered to

regard objectively and from the outside the institution in the name of which

his natural inclinations are condemned. He no longer regards the family as

natural and appropriate. He recognizes it as arbitrary and so he can

identify its faults, which are obviously legion. As a consequence it is not

surprising that Tolstoy’s bleak picture of the family group should be

intertwined with the expression of his homosexual longings. By way of aside,

I think there is also a plausible explanation for the apparent pre-eminence

of homosexuals in the arts and sciences. It is not, for one thing, entirely

clear that homosexuals do show prominence in the arts and sciences in

greater numbers than their actual percentage of the population as a whole.

And the idea that homosexuality might somehow be tied to greater

intelligence or creative powers, while not obviously wrong, lacks a clear

causal narrative and so causes us to favor alternative explanations. Until

biological reasons are discovered that favor homosexuals’ mental capacities,

simple common sense explanations will continue to appear much more likely.

For example, homosexuals are not burdened by the emotional and time demands

of breeding and so they can devote more time to the pursuit of cultural and

other activities. Those non-homosexuals who rejected family participation

(Descartes and Mondrian come to mind) also profited from their greater

amount of free time. It would be interesting to see what the effects would

be if some homosexuals were granted their wish and allowed to form pseudo

families.

Note: I don’t read Russian

and I’ll be the first to admit that some of what I have to say above depends

on the meaning of an English word or phrase. If the Russian has been

misrepresented, then my essay is not about Tolstoy at all but about Aylmer

Maude et al.

|